Khairabad (Rajasthan): The unofficial rule in Khairabad is clear. After a girl hits puberty, she can continue her education, but only in an all-girls school.

Demographically, this hamlet in Rajasthan’s Khairabad block in Kota district has a majority of “lower castes”. Even though the savarnas are a numeric minority, they are able to assert their will. Muslims are in a minority.

Decades ago, savarnas in Khairabad had handed over a piece of land to government authorities for establishing an all-girls school. The purpose was simple – permanently shut the door on co-education. Today, around 300 middle-school girls are enrolled in this sole government-run all-girls school, which runs for classes six to ten.

Since children below class six haven’t yet hit puberty, they are allowed to attend co-educational institutions.

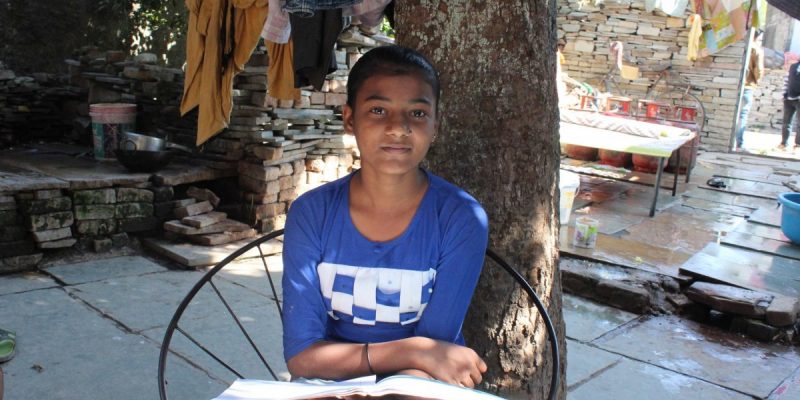

Aliya is a class three student admitted in a private co-ed school in Khairabad. Her father says, “Abhi toh chhoti hai, samajhdhar nahi hai. Chatti mein sayani ho jayegi tab school badalna padega (She is naive now, she doesn’t understand things. In class six, when she will hit puberty, we will have to change her school).”

Aliya, student of class three, is free to study in a co-ed school up till class five. She is studying in a private co-ed school at present. Photo: Shruti Jain

“A girls’ school provides a safe environment for adolescent girls,” says Himendra Sharma. His wife, Sushila Sharma, was the former sarpanch, but he handled the post on her behalf. According to Sharma, a “safe environment” is one where the interaction between girls and boys – particularly those from different castes – is not possible.

The people of Khairabad believe that a co-ed school could become a breeding ground for inter-caste and inter-faith marriages, which would dismantle their long-preserved caste hierarchy. Their diktat to avoid this has largely been normalised…until now. The state government has chosen the girls’ school in the village to be part of its scheme to set up English-medium schools at the block-level.

If the school is transformed to English medium, the school will immediately stop being all girls, since the government does not want gender bias in its implementation of this scheme. Khairabad, though, views this change as an attack on the status quo – and girls are being told to drop out of school for the “greater good”.

§

Alisha’s report card form last year, showing she got a 100 on 100 in English. Photo: Shruti Jain

Alisha can read all the English words that appear on television during advertisements. In the last academic session, she was only one in the entire school who scored 100 on 100 in English.

Despite this outstanding performance, her parents have discontinued her schooling. “A ‘case’ had happened within our family and since then, there is a lot of pressure to remain careful,” Alisha’s father Amjad Noor says reticently.

Noor’s niece, who went to a co-ed school, fell in love with a Hindu man and eloped. This is what he refers to as a “case”. Nothing bothers him more than the thought of Alisha going to a co-ed school.

Up till class five, Alisha had studies at a small private school. This year, as per Khairabad’s norm, she was supposed to join the all-girls school. But since it turned into a co-ed, her family no longer thinks she should.

Also read: How Meritorious and Inclusive Are Our Institutions of Higher Education?

Alisha has spent this whole year praying for things to change. Whenever she finds Noor in a good mood, she asks him to let her study at the girls’ school in the adjoining village. But he immediately rebuffs her request, saying that would mean the unnecessary additional responsibility of dropping her and picking her up everyday.

The Khairabad middle school is located in the lane adjacent to their house, but the school Alisha suggested to Noor is a half hour’s walk away. “Who has so much time? And then the constant tension of her safety all day,” says Noor.

Another reason why he doesn’t want to make any effort to ensure Alisha’s schooling continues is that his wife recently gave birth to a son – and he has become the priority. “I’ve lost my income in the pandemic,” he says. “But there is an added responsibility [of my son] too. I want to focus on improving my financial condition rather than running after her education.”

For now, Alisha has bought some time. She has managed to convince her father to not take her transfer certificate from the private school she was studying till last year, hoping that he might change his mind in this period.

Alisha with her father Amjad Noor and younger brother at her home in Khairabad. Photo: Shruti Jain

§

After noting down a sentence from her English textbook, Harshita picks up her pocket-sized English-to-Hindi dictionary and meticulously hunts for its meaning in Hindi – one word at a time.

To make this exercise simpler, she has written the alphabet on the front page of her notebook, for quick reference.

After finding meanings to all the constituting words of the sentence, she combines them to form a loosely translated sentence in Hindi. “This will work for me,” she says, with the satisfaction of having discovered an indigenous way to acclimatise to the new language.

Harshita is a class nine student from a Dalit family in Khairabad. For all these years, her medium of instruction has been Hindi. This is the first time she is studying other subjects in English.

She was not prepared for this abrupt change and would have never opted for English, if her opinion had been asked. But now, there is no alternative. The only all-girls school, because of which she was somehow able to continue her education, has now converted to an English medium school.

Harshita is being able to continue in the recently established English medium coed school this year only because there was no compulsion to be physically present. Photo: Shruti Jain

Harshita isn’t sure if she will be able to continue her education next year. “We don’t want to discontinue her education. We’ll see what other parents do and then decide,” says her mother, Girija. “English medium is good but it would have been better if had not turned into a boys’ school [referring to it becoming co-ed].”

§

This year, some girls are being allowed to continue in the co-ed school because classes are taking place online. But chances of parents letting them into the same space as boys on a regular basis are low.

This is a serious problem; Khairabad already has quite a disturbing literacy trend. As per the 2011 Census, the male literacy here is 81.53%, while the female literacy rate is merely 53.46%. These rates are similar to the rest of the state.

Also read: A Teacher’s Pain: Meet ‘COVID Challan’ Targets or Get a Show-Cause Notice

A latest report based on a National Statistical Office (NSO) survey has revealed that Rajasthan has a very poor record on girls’ education. It has recorded the lowest female literacy rate (57.6%) in the country. The report further highlighted that 43.7% of the girls and women in Rajasthan above five years of age have never had any formal education.

This existing problem may be significantly exacerbated if parents pull girls out of schools because they are becoming co-ed.

The recently converted English medium school in Khairabad. Photo: Shruti Jain

Although the fallout was inevitable, the government made no efforts to deal with it. When talks around the selection of Khairabad’s all-girls school for the scheme gained momentum, the school management committee, run largely by savarna parents, spared no effort to resist it.

Letter written by the school committee to the education officer requesting him not to nominate Khairabad’s girls-only school for conversion to English medium.

In a letter to the chief block educational officer (CBEO) of the block, who has the authority to select one school from his jurisdiction and forward it to the government for consideration, the committee asked him. not to nominate the girls-only school. It clearly mentioned that if boys join the school, girls will be made to drop out.

It further suggested that the government should consider upgrading the all-girls school, which is only up to class ten, till class twelve, rather than converting it into an English-medium school just up to class eight.

“The school was formally approved to be upgraded [to have classes till twelve] in 2019 itself,” says Sharma. “Then, this English medium proposal came out of nowhere and even got accepted without our consent.”

§

The setting up of English-medium schools under the scheme in rural areas has taken on a political colour, primarily because the guidelines say that the nomination of schools must be made upon the recommendation of elected representatives in the area.

This has caused a competition among MLAs and sarpanches in areas where the two are either affiliated to different political parties or belong to different castes. Both see it as an opportunity to solidify their vote bank by crediting themselves for bringing English education to rural areas.

In Khairabad, the village representatives are Brahmins, while the former Congress MLA belongs to the Dalit community. The Brahmins are not in favour of having a co-ed school, even if education in English is acceptable to them.

They hold the former MLA, Ram Bairwa, responsible for ‘eliminating’ the sole all-girls school in Khairabad. They believe the “lower castes” are at an “advantageous” position if inter-caste marriages occur.

“Don’t we know that he is doing it all to appease the Bairwa community?” says former ‘sarpanch-pati‘ Himendra Sharma.

Bairwa, on the other hand, says that the demand for having an English-medium school came from the village itself. “There was a massive competition among various villages in this block to have the English-medium school in their area. We are lucky to have one.”

The Mahatma Gandhi Government (English-Medium) School Scheme was launched by the ruling Congress government in Rajasthan in 2019, with the objective of providing at least one government-run school in every district and block that will have English as the medium of instruction. Until now, government schools in Rajasthan affiliated to the state board of education taught in Hindi.

Guidelines of the Mahatma Gandhi Government English-Medium School Scheme, mentioning that the development of schools will be managed through donations.

However, this is not the first time that the state government has thought about creating English-medium government schools, or even started the process. A similar scheme called the Swami Vivekanand Model School Scheme was launched by the previous Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) government in the state in 2016.

Although the objective of the two schemes is largely the same, there are two major differences. First, the schools under the former are affiliated to the state board of education, while the later to the central board of secondary education (CBSE).

Second, and a more significant difference, is that the Mahatma Gandhi scheme has no separate budget, while the Swami Vivekanand did.

As per the guidelines of the scheme, the Mahatma Gandhi schools are dependent on donations for their development, either from the ‘Bhamashah’ or multi-national companies under corporate social responsibility contributions. (In Rajasthan, people who donate money to charity are called ‘Bhamashah’ locally.)

The school committees, which usually pay for all development-related expenses, now feel affronted. The committee in Khairabad says that it feels that its donations have been misappropriated.

“We had put in so much [money] so that the girls could study safely. Now, if the boys will come, what purpose will it serve?” says Naveen Sharma, a committee member.

The scheme has no express provision stating that only all-girls schools must be converted into English-medium schools, yet a majority of schools chosen are all-girls ones. The education department says all-girls schools were chosen because they had low enrolment rates as compared to all-boys or co-ed schools. “The quality can be maintained only if the number of students and classes will be limited,” said Vikas Meena, in-charge of the scheme in Jaipur.

Girls dropping out of school on reaching puberty is often linked only to poor menstrual hygiene in schools, due to the lack of functional toilets. But the story of Khairabad suggests that it is only a part of the problem; the motive is to control female sexuality and make sure they are not given a chance to erase or redraw discriminatory societal boundaries.