‘His contributions in setting up transparent precedents of governance are still basically intact despite the cynicism of several of his successors,’ notes Jamini Bhagwati.

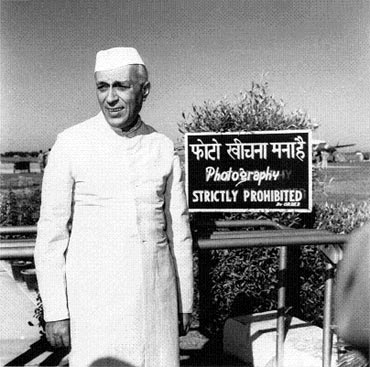

Photograph: Homai Vyrawalla

Nehru was a towering figure in Indian politics for over four decades. His impact on the country overshadows that of all other PMs who have come after him till now. Nehru’s successors did not have his level of wide reading (except P V Narasimha Rao), his capacity to reflect and write, or his ability to make moving speeches.

Nehru’s speech at Independence and when Gandhi passed away, and The Discovery of India, written while he was in prison, are simple and yet relevant even today, and should be compulsory reading in high schools.

Nehru as the first head of India’s central government had the burden of reconciling a range of retrograde and poorly informed attitudes to forge consensus on forward-looking social legislation and government policies.

The enormous domestic, foreign policy and security challenges that Nehru addressed all look simple to face with the benefit of hindsight. Memories have faded about the difficult environment in which India was put together in its present form.

First, a liberal and forward-looking Constitution was adopted based on Nehru’s commitment and that of the freedom-fighting generation of leaders to democracy, which institutionalised legal structures against religious bigotry and feudal mindsets.

Despite low levels of education and widespread illiteracy, basic norms of debate in the national Parliament and state assemblies were established.

His contributions in setting up transparent precedents of governance are still basically intact despite the cynicism of several of his successors.

Nehru’s legacy includes the holding of regular free and fair elections. This achievement alone, which involved the setting up of the Election Commission and all the attendant procedures, separates India from its neighbours to the east, west and north.

In addition, parliamentary committees and the checks and balances of a well-functioning democracy, including a free press and independent judiciary, were institutionalised.

During the Nehru years, educational and specialised institutions were headed by experts rather than those who were close to the ruling party in Delhi. Of course, this had a lot to do with the optimism of a newly independent country.

The foundations of India’s leading scientific and technological institutions were laid during the 1950s. For example, the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Indian Institutes of Technology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences and the Indian Space Research Organisation.

The emphasis was on identifying academics or professionals with proven track records to head institutions of excellence, including in the social sciences.

No other Indian PM has come close to Nehru’s success in building quality institutions which have served the nation.

Nehru was fortunate to have highly gifted professionals and public figures around him who were solely driven by the motivation of nation-building. These included Cabinet colleagues, chief ministers in various states, scientists and a host of other gifted contemporaries without whom several of India’s achievements would not have been possible.

Nehru is criticised for his so-called ‘socialist’ economic policies. The fact is that Nehru’s mixed performance on the economic front was a huge improvement on that of British India.

For instance, inflation was muted during the first ten years after Independence and severe food shortages were averted. Despite an acute shortage of capital, there was significant industrial growth.

John Mathai commented around 1958 that ‘Pandit Nehru like Mahatma Gandhi before him, combined political idealism with a keen sense of political expedience — not in any unworthy sense but in the realisation that idealism bore no fruit unless men’s eyes could be opened to it and their support enlisted in its behalf.’

Well before Independence Nehru was convinced that India would play an important role in international affairs as a large country. At the same time, Nehru felt that India should not get sucked into taking sides between the West led by the US and the Soviet bloc of nations.

However, the India economy would have modernised faster and growth would have accelerated earlier if he had not been so wary about forging closer economic linkages with the West.

Developed democracies were piqued by Nehru’s grandstanding on the world stage without commensurate economic or military weight. Communist China’s leaders felt the same. And, Nehru blundered in the lead-up to the 1962 war with China.

Nehru’s default mode was to trust his own ability to convince others, and this did not necessarily work with heads of government of other countries.

An extremely distressing error that various commentators deliberately or mistakenly make is to speak of Nehru and Indira Gandhi in the same breath. For instance, use of the phrase Nehru-Gandhi dynasty, as if similar values and principles governed decision making during the Nehru era and the Indira Gandhi years.

Nehru’s missteps were more in the realm of foreign policy and were just that — mistakes. Starting with Indira Gandhi and subsequently other PMs, decisions were often driven by personal, family or partisan interests.

The only way that Nehru and Indira Gandhi were related was that he was a doting father and she a loving daughter. In everything to do with modes of governance, building of institutions, transparency and personal values they were as different as day and night.

Was Nehru a ‘huge banyan tree’ that did not allow anything to grow beneath it? From various accounts, it does seem that Nehru appeared worn out by 1959-1960 by the pressures of office and particularly the road travel for electioneering. Unfortunately, no one close to him persuaded him to groom a successor.

After 1957 he could have continued as Congress president but without the day-to-day responsibilities of head of government. It would have helped the cause of Indian democracy had Nehru persuaded Parliament to pass legislation that limits an Indian PM to two five-year terms or ten years in total if there are mid-term elections.

Such a move by Nehru would have probably sailed through and would have nipped in the bud the possibility of personality cults developing around any subsequent Indian PM.

Given Nehru’s school and university education in England, he unwittingly perpetuated an English-speaking elitism. The Indian elite in all walks of life, not just politics, was English speaking during the Nehru era. To the extent that the vernacular-speaking masses did not understand the English used by decision makers, there was bound to be a pushback in a representative democracy.

The exclusive use of local languages for government forms and applications started in the south and has now gradually spread all over the country.

This pride in India’s well-developed regional languages and culture is natural. However, as it descends to chauvinism and rejection of English, average Indians risk losing this useful medium of communication with the rest of the world.

Memoirs of civil servants close to Nehru suggest that he could be quick to anger yet democratic in his outlook and warm in personal interaction.

Nehru’s achievements and mistakes are better understood if he is humanised rather than put on a pedestal. He had several of the usual human weaknesses yet an immeasurable love for his country.

Nehru’s conduct and decisions indicate that he had two out of the 3 Cs — Character and Charisma — in abundant measure. There can be no question about his Character given the many sacrifices in his personal life and unwavering commitment to the Indian people.

It is in Competence that he may be faulted in some measure on foreign policy and national security matters. On economic policies, he followed what was the prevailing wisdom of the time and considered appropriate by a majority of domestic and internationally renowned economists.

All said and done, it is likely that without Nehru at the start, there may still have been a continuing ‘idea of India’, but not as an undivided, independent and democratic nation.

Excerpted from The Promise Of India: How Prime Ministers Nehru To Modi Shaped The Nation (1947–2019) by Jaimini Bhagwati, with the kind permission of the publishers, Penguin Random House India.