For the first seven years of my life, I was a British Indian subject. Of that, I remember little. By the time I could have my own recollections and experiences of Indian public life, I was a citizen. These recollections and experiences, like those of my coevals, constitute a saga of deepening disenchantment.

The experience of subjection, which the innocence of childhood saved me from, has come to me amply during a life spent in studying colonial India. For close to 60 years I have inhabited subject India and independent India simultaneously. Along with witnessing the vicissitudes of the Indian Republic, I have closely followed a whole range of developments in colonial India. I have suffered with my educated forbears the repression, the pain, and the humiliation of subjection. I know the dreams they dreamt of a new, independent India, and the way they strove for those dreams. I know the oppressive colonial apparatus they had to contend with, including its law courts.

I cannot not compare the two. More so when, as now, life in the Indian Republic becomes claustrophobic and forces the question: Have we, as citizens, been true to the dreams we had dreamt and the resolves we had made as subjects?

The blunt answer is that we are no longer citizens. We are subjects, like we were in enslaved India. Worse, if truth dared be told.

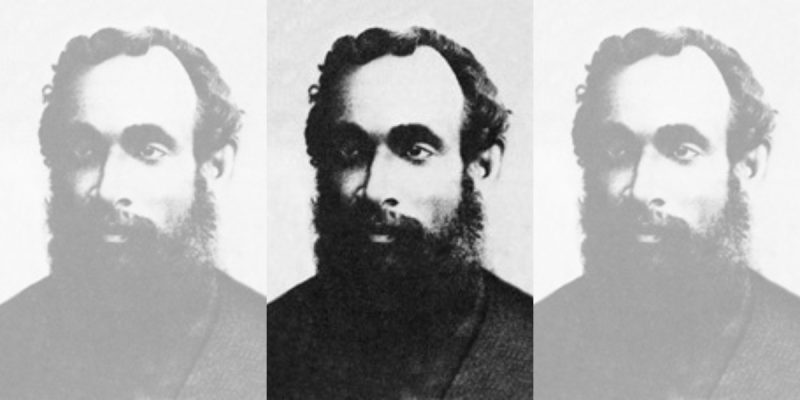

Not many today would remember Surendranath Banerjea, that pioneering figure among the makers of modern India. A whole decade before the Indian National Congress – of which also he was a prominent leader – Banerjea, as one of the moving spirits behind the Indian Association, provided an organisational basis for pan-Indian nationalist politics. He enthused thousands of his compatriots to dedicate themselves – to recall his autobiography, A Nation in Making – to the making of the Indian nation.

Surendranath Banerjea

A Nation in Making

The mention of Surendranath Banerjea brings to mind many memories. One of these is particularly pertinent for us today in view of the unfortunate salience the issue of contempt of court has acquired. Banerjea was charged with contempt of court for writing an editorial in his English weekly, The Bengalee, and sent to jail by Justice Norris of the Calcutta high court. This resulted in protests and hartals all over Bengal and as far as Maharashtra and the Panjab.

The most memorable protest, though, came from a serving Indian official, Behari Lal Gupta. Gupta was one of the four Indians, including Surendranath Banerjea, who had entered the ICS in the same year, 1869. Gupta was in office when the news of Banerjea’s sentence reached him. After finishing the day’s work, he went straight to the jail and met Banerjea.

There is another reason for remembering Banerjea. It relates to the recent spate of official and officially countenanced charges of sedition and treason against honest, courageous and committed individuals, charges that our law courts have demonstrated an unprecedented readiness to believe and admit.

Something similar happened when, soon after assuming the viceroyalty of India, Lytton (1876-1880) made it his top priority to crush what he saw as widespread disloyalty and sedition. This is what Banerjea’s The Bengalee said in its issue of September 1, 1877: “When a Government is determined on finding sedition, there will be little difficulty in finding it.” Indians, The Bengalee added, were determined to resist the “wicked tyrants”.

The Bengalee was not alone. No respectable Indian newspaper or periodical, neither in English nor in Indian languages, succumbed before the Lytton administration’s coercive policies and pronouncements. Even the draconian Vernacular Press Act failed to gag the Indian language Press. The Act was removed forthwith by his successor.

Let alone the subject Indians, Lytton did not go unchallenged even among his councillors. One of them, Arthur Hobhouse, was particularly unsparing in his principled opposition to the imperious viceroy. The worst that happened to the dissenting Hobhouse was to get the sobriquet “evil Genius” from Lytton even as the Indians looked upon him “as an Englishman to the core”.

How does one explain this contrast between the intrepidity of the subject and the obsequiousness of the free? Or the absence of exceptions like Hobhouse and Gupta within the ruling dispensation of the free?

The current phenomenon of Indians being reduced to subjects takes the mind back to a striking epistolary exchange between Lytton and his boss in London, the Secretary of State for India, Lord Salisbury. Extraordinarily repressive as Lytton’s regime was, even more extraordinary was the philosophy of governance that he shared with his boss. Writing to Salisbury on May 11, 1876, Lytton dismissed as a “fundamental political mistake” the belief that India could be held by good government, “that is to say, by improving the conditions of the Ryots, strictly administering justice, and spending immense sums on irrigation works, & c.”

Salisbury agreed heartily and, in his reply of June 9, explicated the underlying logic of Lytton’s formulation. The masses, he wrote, ”must never be counted upon to resist their real enemies, or sustain their real friends at the right moment.”

None of this was meant for public consumption. The overt official discourse – the debates in the Viceroy’s Council, the speeches of officials, etc. – remained sedulously couched in the lofty language of the ‘White Man’s Burden’ and ‘Civilising Mission.’ Had I not had access to the confidential correspondence between Lytton and Salisbury, I would not have understood the deeper springs of their decisions and actions.

This carries a disconcerting resemblance with the present of the Indian Republic. Illustrations are galore. Let us just concentrate on that March evening when the Prime Minister announced a nationwide lockdown, beginning the same mid-night. Hard for anyone, except for the super-rich, this created an impossible situation for the poor, which means the overwhelming majority of Indians.

The most vulnerable of them were – are – the daily wage-earners and self-employed who had migrated from the countryside to large cities. They had no savings to stave off eviction and starvation. As for the self-quarantine and the social distancing that the lockdown was meant to ensure, it was impossible for them, given the way they were cramped together in tiny accommodations.

The Prime Minister considered it adequate to appeal to the employers to keep paying their workers, and to the landlords not to evict their poor tenants for non-payment of rents, and to promise, on the part of the government, free food and some cash to the needy. Did he believe that this would do? Who believed it would?

Human cost of the lockdown at midnight: scattered on the railway track the meagre belongings of 16 migrant labourers who were run over by a goods train in Aurangabad on May 8. Photo: Reuters

When, expectedly, the inevitable happened, and the poor felt compelled to come out and trek back to the uncertain security of their distant homes, the government let loose its police on them. The whole country saw what happened. Only our government, unsurprisingly, and our Supreme Court, surprisingly, did not. The former submitted an affidavit which belied what the whole country had witnessed. The latter accepted it as the truth.

What does this mean? Let us for the moment steer clear of considerations like humanity. What does this want of concern for the poor, especially the migrant labourers, mean in terms of conventional electoral wisdom? Does this mean that the ruling party believes that it can dispense with the votes of this massive segment of the country’s electorate? Clearly not. It would rather appear that the party leaves its miracle-performing leader free to decide.

And the leader, following his 2019 re-election, has made the happy discovery that good government – people’s well-being – is irrelevant for retaining power. No matter how badly they are treated today, he will manage, when required, to inveigle them into supporting him. They will not “resist their real enemies,” and they will have no “real friends” to turn to.

Of course, the leader will not say so, just as Lytton and Salisbury did not. Citizens remain citizens not by virtue of the rights enshrined in the constitution they gave themselves in the wake of freedom. They remain citizens by virtue of the deterrence they exercise through the constant threat of an adverse electoral verdict. Given that this leader beguiles like no one before, and also that we are prone to be beguiled like never before, that deterrence is all but gone.

Citizens also hope to remain citizens through the constitutional safeguard of an independent judiciary. As the ultimate protector of the citizens’ rights, our higher judiciary, particularly the apex court, has had a chequered history. It has alternated between institutional glory and shame. These alternations, including the judiciary’s far from reassuring present moment, can be understood only in terms of the larger dynamics of the Indian society.

That will require a separate exercise. Still, because the protection of the poor and the vulnerable is of profound significance, let me return to the apex court’s acceptance of the government’s affidavit regarding the flight of the migrant workers. Let us, again, set aside human considerations, though they can, even technically, be admissible in a matter involving justice, equity and good conscience. The merits of the affidavit apart, the honourable justices seemingly forgot the principle that governs what they do day in and day out: audi alteram partem – hear the other party. The other party, consequently, was exposed to colossal, avoidable damage.

Who, in this season of punitive fines, will be forced to compensate for that damage?

The honourable justices took up this matter when it was too late and claimed that they were taking it up suo motu. Yet another judicial maxim was overlooked. Delay in justice, in this case, arguably meant injustice.

With a leader who can dare dismiss good government as irrelevant, and an apex court that inspires little confidence, we the citizens-turned-subjects of India, must reflect on how we have failed ourselves and reached where we are. Knowing that it is never too late to begin anew.

Sudhir Chandra is the author of Dependence and Disillusionment: Emergence of National Consciousness in Later Nineteenth Century India (Oxford University Press) and Gandhi: An Impossible Possibility (Routledge).