Twenty one years ago, the Indian Army and Indian Air Force fought a bloody and bitter war to evict Pakistani intruders from the icy heights in Kargil.

Air Commodore Nitin Sathe (retd) salutes the lesser known heroes of the Kargil War.

A new series.

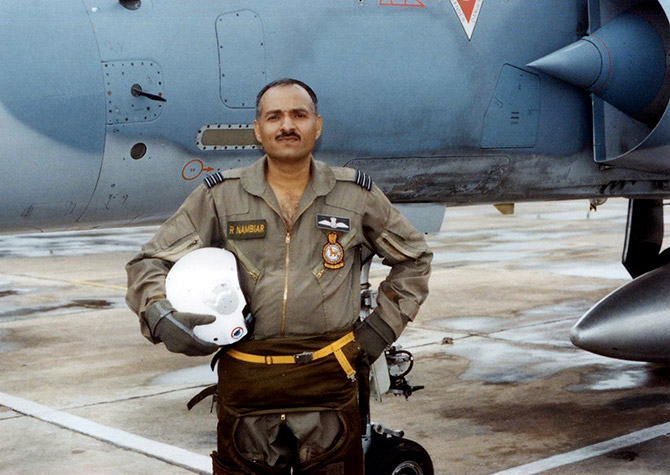

Air Marshal Raghunath Nambiar (retd)

IMAGE: Then Wing Commander Raghunath Nambiar during the Kargil War in 1999. All Photographs: Kind courtesy Air Marshal Raghunath Nambiar

I heard about the first drop of laser guided bombs from Air Marshal Raghunath Nambiar, who was then a wing commander posted at the Gwalior air base (which was home to the Mirages) looking after flight safety aspects.

Namby sir, as he is known in the IAF, was a very experienced pilot on the Mirage 2000 with almost 2,000 hours on the aircraft and he had had the privilege to fly and test many other types of aeroplanes as an experimental test pilot.

He was augmented to the ‘Battle Axes’ squadron for flying duties as soon as it moved to Adampur for the operations.

“I had the target in sight, on my scope well before we reached the weapon release line.”

“We were firing at the six-seven white tents on Tiger Hill with one laser guided bomb each.”

“But there was a problem. At 28,000 feet, we had a very strong component of cross wind of almost 70 knots (130 kmph) which would not help in delivering the weapon on to the target.”

“A quick decision was made and we descended to 26,000 feet where the winds were within acceptable limits ran in towards the target all systems ‘On’ for sending the bomb to its destination.”

“I pressed the trigger and the aircraft bucked like a horse — losing 600 kg of weight from under its belly.”

“The bombs were on the way now and as I turned the aircraft away with my sights slaved to the target, I waited with bated breath seeing the small screen in front of me.”

“The 30 seconds of bomb flight seemed like eternity and then whoosh! The entire screen went white showing the impact on the tents.”

“We were elated after tasting first blood and hoped for a quick victory by the ground forces as they marched forward to mop up whatever opposition was left on Tiger Hill.”

IMAGE: Then Wing Commander Raghunath Nambiar during the Kargil War in 1999.

“The sortie planning had started two days earlier.”

“On the evening of June 22 we had received orders to attack enemy positions on Tiger Hill the next day.”

“The target as shown in the photographs provided appeared to be 6 to 7 white tents on top of the hill.”

“Takeoff was planned at 0630 hours from Adampur with escorts being provided by 2 more Mirage 2000s from Ambala”.

“The rendezvous happened in the air as planned and all four aircraft set course for the target.”

“Tiger Hill has a unique shape when seen in photographs.”

“From the heights the Mirages were flying, all the mountains merge into one big mass of jagged rocks with valleys appearing as dark lines.”

“The only feature that stood out in this area was K2 which towered above this mass at 28,251 feet, just a couple of thousand feet below the height they were flying.”

“We had the electronics in our aeroplane which we were thankful for. Searching for the target with bare eyes was like searching for the needle in the haystack but due to the technology, we had a clear picture of the seven tents perched against the rocky background on our scopes.”

As the Mirages got nearer to the firing distance the pilots realised there was a small fuzz of a cloud covering the target area and ‘lasing’ the target and thereafter guiding it on the laser beam wasn’t possible.

Due to this constraint, they set up an orbit and conserved fuel to wait for the cloud to move out.

Luck was on the Pakistani side that morning.

The cloud persisted and the aircraft had to return without letting go their bombs.

The intruders were safe for another day on the hill.

“As we turned away from the target, Monish (the pilot in the second seat) yelled at me ‘Flare left!’, indicating a missile launch. I instantly throttled back to idle power and hauled the aircraft upward in a steep left turn and commenced dropping flares.”

“I did not spot the tiny shoulder launched missile, but Monish did see it climb towards us and thereafter fall away as we were outside its envelope.”

The sortie was re-planned for the next day. Air Chief Marshal A Y Tipnis — the then chief of the air staff — flew to Adampur and decided to join in for the mission.

A third fighter was planned in which the Chief flew in the rear seat to get a firsthand experience of the attack/conflict.

“As the bombs hit the target we went around the area looking for any more signs of the enemy.”

On the return leg the Mirages flew over Tiger Hill at a lower height to film the area and assess the damage.

The smoke had cleared and nothing was left on top of the hill.

After they landed, the photo films were analysed.

The photos clearly showed four soldiers running inside the camp area just before the bomb impact.

IMAGE: Air Marshal Raghunath Nambiar.

Another pilot, who flew on the mission and did not want to be named for this feature, told me that he counted between 16 to 18 missiles fired upon the attacking formation that morning.

Indian ground forces were quick to capitalise on the degradation of the enemy and were able to take back the heights of Tiger Hill, albeit after a bloody battle.

Munto Dhalo was an important logistics base for the Pakistani intruders.

It had a road head very close to the camp and so it was easy for the enemy to stockpile their stores in good quantity.

This base was used as a supply point to deliver rations, ammunition and other war fighting wherewithal to the heights occupied in the area.

The post was well fortified since it was important for their survival.

Taking out this post, therefore, became extremely important for the IAF.

Another pilot, who still serves in the IAF, was tasked to carry out an attack at this camp.

“We used the 250 kg Spanish bombs to destroy these hardened bunkers which held the enemy stores.”

“We destroyed the camp at Munto Dhalo completely.”

With that, the sustenance of the troops on the hilltops became untenable and the Pakistani troops now knew that their end was near.

“We heard many panic-stricken radio intercepts to their HQ for supplies and sensed that we had broken their logistics backbone; so vital for their sustenance in that area.”

“They had no choice, but to commence their withdrawal back into their country.”

IMAGE: Air Marshal Raghunath Nambiar.

Another Mirage pilot, who also wishes to remain incognito, told me about the difficulties of identification of friend or foe (IFF) during the sorties flown in the war zone.

All the attacks were planned with adequate escorts so as to thwart any misadventure by the opposing side.

“In the absence of radar cover in that area as well as compatible IFF equipment on the differing types of aircraft flying in that area, it was good luck and some clear thinking on our part that we did not shoot down our own aircraft in the fog of war,” says the pilot who flew extensively during the operations.

“We used many innovative methods so as to identify our own guys. Aircraft were flying from many bases from as south as Adampur; and although briefings were carried out over the phone, there were always gray areas.”

“One day, there was a large package of aircraft milling around the area around Drass and I was giving them cover from right above at 40,000 feet.”

“As I was scanning the area for intruders on my radar, I could see two unidentified blips on my scope.”

“To ascertain whether they were friendly, I gave a call, ‘All aircraft to turn 180 degrees’, I saw that all except two turned around and obeyed my instructions. I locked onto the two fellows who hadn’t heeded my call and started going towards them to ascertain visually if I could.”

“It turned out that that the two blips were, in fact, our own Jaguars who were not on our radio channel due to some reason. In actual combat, I would have let my missiles go but better sense prevailed and we prevented severe embarrassment for the country and the IAF,” remembers the battle hardened pilot.

There were many such close shaves which became jokes to laugh over a drink in the evening, but on a serious note, the IAF realised that it needed to have better IFF systems — common to all aircraft in its inventory — to prevent fratricide in future conflicts.

Air Commodore Nitin Sathe retired from the Indian Air Force in February 2020 after 35 distinguished years of service in the IAF.

He is the author of three books including Tsunami 2004: The IAF Story: a Few Good Men & the Angry Sea about how the IAF rebuilt its Car Nicobar airbase after the December 26, 2004 tsunami completely devastated it.

Feature Production: Aslam Hunani/KhabriBaba.com