After the Ladakh fiasco where Xi Jinping did not expect the Indian Army to resist his land-grabbing tactics, he has to save face before his colleagues in the Communist party.

To bring the threat of a mega-dam to the northern Indian border is a clever move, observes Claude Arpi.

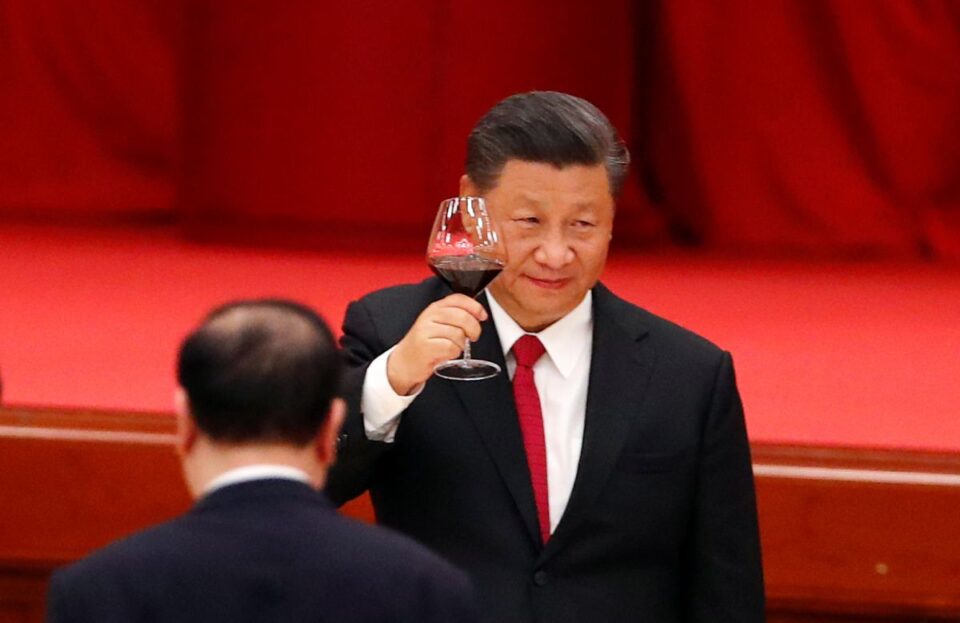

IMAGE: Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Communist party of China, at the National Day reception in Beijing, September 30, 2020, on the eve of the 71st anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Photograph: Thomas Peter/Reuters

On the occasion of the New Year, President Xi Jinping called the Communist party ‘a gigantic vessel that navigates China’s stable and long-term development’.

‘Upholding the principle of putting people first and remaining true to our founding mission, we can break the waves to reach the destination of realising the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation…’ Xi declared.

‘China will embark on a new journey of development in 2021 and strive to achieve socialist modernisation by the year 2035.’

Traditionally, the Chinese people’s respect for their emperor increases when he undertakes projects that no human mind can conceive of.

After all, the emperor is the Son of Heaven, and only in Heaven can projects such as the Grand Canal or the Great Wall be dreamt of.

It is also the emperor’s role to bring Heaven’s vision down on earth. If he fails, his Mandate is terminated by Heaven and a Revolution or a Rebellion occurs.

This is what might soon happen to Xi Jinping, but in the meantime, he is thinking big.

The Seventh Tibet Work Forum (TWF), a mega meeting which decides the fate of Tibet for years to come (to which rare Tibetans are invited), was held in Beijing on August 28 and 29, 2020.

The Seventh TWF was a crucial event not only as it concerns the fate of the Roof of the World, but also for the presently tense Indian frontiers and the precarious situation in Ladakh.

The TWF usually defines the policies for China’s western border (this explains the presence of the entire Central Military Commission, as well as the service chiefs, including the chief of the PLA Navy at the Forum).

During the meeting, infrastructure development was linked with Border Defence; the construction of Xiaokang (moderately well-off) villages on India’s border, was mentioned.

A few weeks later, some massive projects were announced. First, the Pai-Metok (Pai-Mo) Highway linking Nyingchi to Metok, north of the Upper Siang district in Arunachal Pradesh, will be opened in July 2021.

After the completion of the highway, the length of the road from Nyingchi city to Metok county will be shortened from 346 kilometres to 180 kilometres and the driving time will be shortened from 11 hours to 4.5 hours.

The highway starts in Pai Town in Nyingchi’s Milin county and uses a long tunnel to pass through the Doshong-la mountain, ending south of Metok town, close to the Indian border (Tuting Circle).

Though only 67 kilometres long, in strategic terms the highway will be a game-changer and greatly accelerate the developments of new model villages, and therefore relocation of populations on the border. But more importantly, it will pave the way for a mega hydropower plant (HPP).

In December 2020, The Global Times announced Beijing’s plan to build a large hydropower plant on the Yarlung Tsangpo river (which becomes the Siang and later the Brahmaputra in India).

The tabloid admitted that ‘it has raised concerns in India over potential political and ecological threats as the river passes through Southwest China, India and Bangladesh’. It, however, asserted that Chinese experts ‘refuted the claim that Chinese hydropower project has political aims, and said the project could help alleviate power shortage problem in northern India and boost the regional economy.’

The Metok county government confirmed that the project would be built north of the McMahon Line.

The Global Times, a mouthpiece of the Communist party, added: ‘The head of the Power Construction Corp of China suggested the planned hydropower station – which is expected to have three times as much generating capacity as the world-leading Three Gorges power station — aims to maintain water resources and domestic security.’

IMAGE: The route of the Brahmaputra river. Photograph: Kind courtesy Wikimedia Commons

After the Ladakh fiasco where Xi Jinping did not expect the Indian Army to resist his land-grabbing tactics (‘salami slicing’ or whatever you call it), he has to save face before his colleagues of the Communist party’s Central Committee and Politburo.

To bring the threat of a mega-dam to the northern Indian border is a clever move. The fact that the news appeared in The Global Times, the mouthpiece of the Communist party of China, is telling.

Xi believes that the party (meaning himself) is always right. How could he have blundered in Ladakh; to regain some standing, he has to intimidate India.

A mega-dam or hydropower plant, thrice the size of the Three Gorges Dam, threatening life in the North East is the best way to divert the attention from the Pangong Tso.

Photograph: Kind courtesy tibettravel.org

Already in 2016, The China Daily had reported the construction of a 1,629-kilometre Sichuan-Tibet railway. It has now entered a crucial phase.

At that time, Lobsang Gyaltsen, the then chairman of the Tibet Autonomous Region government, (Gyaltsen recently ‘disappeared’ like Alibaba’s Jack Ma), announced during the fourth session of the TAR’s 10th People’s Congress in Lhasa: ‘The government will start a preliminary survey and research of the Kangding-Nyingchi railway project this year, and accelerate the construction of Sichuan-Tibet railway in the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) period.’

Kangding is known as Dardo or Dartsedo in Tibet; it is today the capital city of the Gartse Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture.

The railway will connect Lhasa to Chengdu; it will be divided into three sections from west to east: Lhasa-Nyingchi, Nyingchi-Kangding, Kangding-Chengdu.

The railway line will run some 1,000 km on the Tibetan plateau. The construction of the western and the eastern sections started last year. The entire project is expected to be completed in the mid-2030s.

The China Daily quoted Lin Shijin, a senior civil engineer at China Railway Corp, who stated: ‘The accumulated height it will climb reaches more than 14,000 meters, and it will cross many fault zones.’

‘It’s like the largest rollercoaster in the world. With a designed service life of 100 years, it is believed to be one of the most difficult railway projects to build on Earth…’

‘It presents difficulties to overcome, such as avalanches, landslides, earthquakes, terrestrial heat, karst caves and underground streams, yet, it is still a worthwhile project.’

It takes 42 hours by train and three days by road to travel today from Chengdu to Lhasa; the new rail line will shorten the travel time to less than 15 hours.

It will have incalculable strategic implications for India as the train will pass close to the Indian border, north of the McMahon Line in Nyingchi city.

An even more formidable project is a new road between Xinjiang and Tibet.

The National Highway 216 (known as G216) may one day link northern Xinjiang to Kyirong county in Tibet (the border town with Nepal).

It would be the second road link between the two restive provinces of Tibet and Xinjiang (the first one is the G219 or Aksai Chin road, running through Indian territory).

For obvious reasons, Beijing does not want to announce it as yet; the road should serve the under-developed parts of Gerze county of Western Tibet (Ngari prefecture) …and reached Nepal.

It is probably an important part of the Belt and Road Initiative between Central and South Asia, dreamt by Xi Jinping.

But this is not the trickiest part of the project. How will the Chinese engineers cross the Kunlun range?

Once on the plateau, the terrain (probably via Gerze county) will be easier.

Today, many believe that it is impossible to cross the Kunlun.

But Beijing has probably done its homework and studied 19th century Western explorers Sven Hedin and Aurel Stein who moved around the area and found slightly easier passages to cut across the formidable natural barrier.

Last, but not the least, Xi is planning to start a mega lead zinc mining project in Huoshaoyun area, in China-occupied Aksai Chin.

Acording to the Shanghai Nonferrous Metals Network: ‘In September 2016, Xinjiang geological prospecting made a new major breakthrough.’

‘Among them, the Huoshaoyun super large lead-zinc mine has a proven resource of 17.08 million tons, ranking seventh in the world, second in Asia, and first in China.

‘At the end of 2016, Guanghui Zinc, a subsidiary of the Guanghui Group, had tendered for open-pit mining, explosive supply and blasting services at the Huoshaoyun lead-zinc mine. It was initially scheduled to be organised from April 2017 to the end of December 2019. At present, some areas of the Huoshaoyun mine have entered the exploration stage.’

Though the three first projects (the HPP in the Yarlung Tsangpo, the Sichuan Railway and the G216 Highway) all affect India, the last one (mining in the Aksai Chin) is located on Indian territory.

Nobody seems to have thought about the pollution generated by these mines, it is a great tragedy in the making.

Moreover, for India, the development of the ‘dual-use’ (civil and military) infrastructure in the Ladakh sector will take place on a much larger scale than today.

How will the mandarins of New Delhi’s South Block react? They will probably try to keep the information under the carpet as long as possible, not wanting ‘to hurt Chinese sensibilities.’

If they wait too long, it may be too late.

India will face a new fait accompli.

Claude Arpi is a long-time contributor to KhabriBaba.com.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/KhabriBaba.com