About 18 months after its entry in India, a Spotify listener spent an average of 97 minutes on the app, almost ten times more than any other streaming music brand, reports Vanita Kohli-Khandekar.

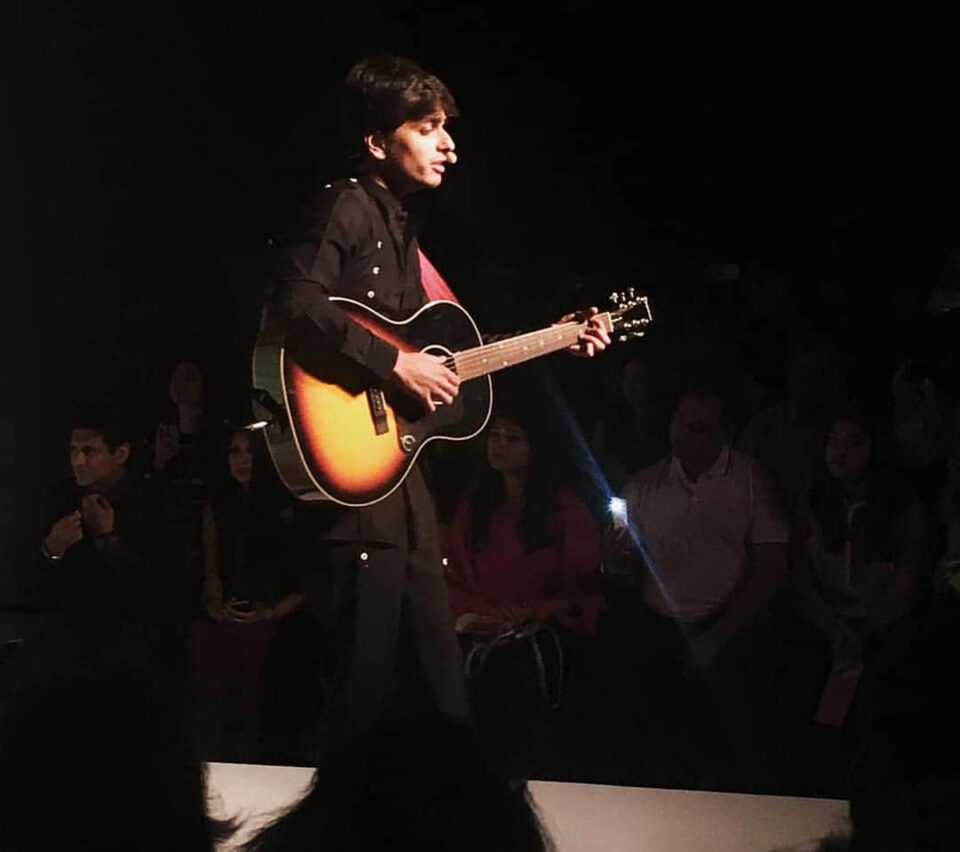

IMAGE: Raghav Meattle performs. Photograph: Kind courtesy Raghav Meattle/Instagram

Korean Pop, or K-Pop, is a lot like the peppy item numbers in Indian films.

Not surprising, then, that India is among the top consumers of K-Pop on Spotify, one of the world’s largest audio streaming platforms.

Apart from that, listeners are spending record time on a mix of independent artistes (Raghav Meattle, Ritviz, Prateek Kuhad), languages (Hindi, Tamil, Punjabi, English et al) and lots of podcasts (The Ranveer Show, Gita for the Young and Restless etc).

In August, about 18 months after its entry in India, a Spotify listener spent an average of 97 minutes on the app, almost ten times more than any other streaming music brand, according to Comscore data.

“It is pure joy that this market needs Spotify as much as Spotify needs India,” says Amarjit Singh Batra, managing director.

“We need companies like Spotify and Apple. They have a one-point agenda — to sell music and collect revenue from consumers based on paid subscribers. They are the Netflix and Hotstar for music,” says one industry insider.

Of Spotify’s 299 million users across 92 countries, a massive 138 million are subscribers. That makes it the largest subscription-driven music app in the world.

This is the first reason that Spotify has found love in India.

The Rs 1,500 crore Indian music industry is deeply under-monetised and in perpetual battle with music pirates or with radio operators and others over its fair share of revenues.

Almost 70 per cent, or over Rs 1,000 crore (Rs 10 billion), comes from streaming music.

But less than two million of the over 130 million Indians who listen to music online pay for it. The rest of them get it free.

The biggest streaming players, Jio Saavn and Gaana, are ad-driven.

So having the world’s largest subscription-driven service pushing the levers of market development delights everyone.

Spotify uses its free, ad-driven service, to get users to sample and sign up for any of its plans ranging from Rs 13 (a day) to Rs 1,189 (for a year).

While it refuses to share subscription numbers, it had 15 million unique listeners in August, according to Comscore data.

If even one million of them are paid, that would be an achievement in this market.

“They have the best product,” said the head of one music label.

That is the second reason Spotify is popular in India.

Users either create their own playlists from its 60 million-plus songs or go with its famed algorithm or choose from four billion curated playlists created by Spotify’s army of music editors.

“We curate experiences. Every playlist is about experiential listening,” says Sneha Singh, music culture and editorial head for India. From 120 at launch, Spotify now has over 500 locally curated playlists in Hindi, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu and other languages.

The third, and arguably biggest, reason is the amount of time, effort and money Spotify is putting into developing the market by discovering and nurturing new artistes, educating them and taking them across the world.

“If you look at the catalogue (in India) there are only half a million songs. In the rest of the world there are 50-60 million. A lot depends on film music (which dominates the market). There are only four songs per film. This has constrained the growth of independents,” says Batra.

Till the nineties there was hardly any market for independent singers in India. Thanks to Channel [V], MTV and others, independents now account for 30 per cent or so of the music industry.

But if the market has to expand, there must be hundreds of thousands of more independents with their own styles, genres and ecosystems a la Alisha Chinai or Lucky Ali in the 1090s.

“We try to stimulate the ecosystem with roadshows, creator workshops,” says Batra.

To this, add Spotify’s global reach.

IMAGE: Armaan Malik performs. Photograph: Kind courtesy Armaan Malik / Instagram

“Armaan Malik was the first Indian artiste on Times Square. There is Prateek Kuhad (whose track found mention in Barack Obama’s favourite playlist for 2019) and G V Prakash,” Batra says.

“We bring upcoming and unknown Indian artistes, put them under a curated playlist. The content goes everywhere; Bekhayali (singer Sachet Tandon) went viral on charts worldwide,” Batra adds.

Spotify for Artistes, a tool for artistes to see data on who is consuming their music and where, has been hugely popular in India, with over 9,600 artistes signing on.

The company has hosted masterclasses with 13,000 artistes from March to August 2020 to educate them on how best to use the app to their advantage. None of the large music or streaming firms has ever done something like this in India.

And there is the investment in podcasts — 16 original Indian podcasts along with many international ones such as the Michelle Obama podcast.

“Globally, 15-20 per cent users listen to podcasts. India is seeing similar traction,” says Batra.

Much of this helps correct decades worth of anomalies in India’s audio markets. For instance, talk radio has never been big on FM, so podcasts are a way of reviving the talk format.

It isn’t all hunky-dory, however.

Globally, 90 per cent of Spotify’s 6.8 billion euros revenue comes from subscription. India, however, gets about 60 per cent of its revenue from advertising.

“In India, the challenge is getting people to pay,” says Batra. Meanwhile, advertising is not simple. “Advertisers think of digital audio as digital radio, which is associated with commuting,” says Arjun Kolady, head of sales. The work, then, lies in helping brands contextualise their advertising — for example, Netflix talking about Korean drama to K-Pop listeners.

All this, however, works well in tier-one, maybe tier-two cities. India has 662 million people online. The next round of growth is expected from 400 million who are largely in small-town and rural India.

“Do they have the wherewithal to understand the next 400 million consumers?” asks the industry observer.

“The first part of the journey was to establish ourselves,” says Batra.

The second starts now.