Statues and monuments to the previously-great and the good seem to be falling at a rapid rate in the new Black Lives Matter-fuelled era. Across the US and Britain, the statues of imperialist Cecil Rhodes at Oxford University, slave-trader Edward Colston in Bristol, have fallen. Confederate symbols on US state flags such as that of Mississippi have been removed. Universities across the European world are under renewed pressure to ‘decolonise the curriculum’ and recognise the contributions of scholars of colour, women, and the global South, to enhance study and teaching of the role of empire and imperialism in the making of the modern world. City, University of London, for example, has dropped Sir John Cass’s name from its Business School because Cass profited from the slave trade.

Intertwined with the ‘tear it down’ movement, and as part of furthering public knowledge of the vagaries of hidden histories, there is a process of uncovering past progressive figures who have slipped away from popular memory. We have the opportunity to tell a more full story of our shared past. One prime candidate for restoration is Dadabhai Naoroji, who inspired Mahatma Gandhi, championed the education and equal rights of girls and women in India, women’s suffrage, opposed poverty in India and in Britain, and championed Irish home rule.

Dadabhai Naoroji, Indian businessman, scholar, and activist, was also the first Asian member of parliament in the British House of Commons. Incredibly, this was way back in 1892, in the Clerkenwell district of the City of London where, of course, City, University of London, is located. A relatively discreet plaque in Naoroji’s honour adorns an exterior wall of Finsbury Town Hall; Naoroji Street, a Clerkenwell backstreet, commemorates him too.

Yet this hardly seems sufficient given Naoroji’s historic significance to Britain and India.

He was a champion of free mass education in India, and once he arrived in Britain he built productive alliances with the “ragged schools” movement leader Mary Carpenter. She, in turn, helped in promoting education for the poor in colonial India.

Naoroji was a skilled and critical economist who used vast caches of hard economic data to describe the real poverty of India and its causes. He rejected the-then conventional economic theory that as economies worked on the basis of “natural laws”, the wealth and poverty of nations was beyond human action. In reports and articles, lectures and testimony at House of Commons’ committees, Naoroji challenged dominant economists, India Office civil servants, and colonial administrators, to show that the poverty of India was the direct result of British rule, especially the taxation that went to finance the Indian government and military.

If the above idea of the role of an economist challenges orthodoxy even today, Naoroji used his economic and statistical research to develop and crystallise political demands for reform and justice – a far cry from the poverty of economics today. His “economic drain” theory of imperialism places him in the company of J.A. Hobson and Henry Hyndman, and brought him to the attention of the leaders of the Second International such as Karl Kautsky and Rosa Luxemburg.

Also Read: Swaraj, Agitation and an Intrepid Spirit: Dadabhai Naoroji’s Final Days

Winning a seat in the House of Commons, however, required a skilled politics. There was no ready-made ethnic India voter base in the 1890s. Naoroji fostered and built political alliances that were transnational, multiracial, and mobilised women suffragists, and working-class voters demanding action on their economic and social rights. This was not narrowly-conceived identity politics of separate struggles that pit one disadvantaged group against another but the politics of building broad fronts of the oppressed to stand together and fight for change.

Naoroji’s example also shows how powerful is precise, meticulously organised knowledge, and the significance of wedding knowledge to politics and movements for change. Education, research, and teaching were central to Naoroji’s life, and politics. A full professor at Elphinstone College in Bombay before departing for England, he served for a time as ‘professor of Gujerati’ at University College, London. And of all the awards and honours heaped on him over his lifetime, the one of which he was most proud was the title “professor”. He seemed to be that very combination of knowledge and action that Karl Marx might have been referring to when he noted that “philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point however is to change it”.

To change the world, Naoroji went to the very heart of world power at that time.

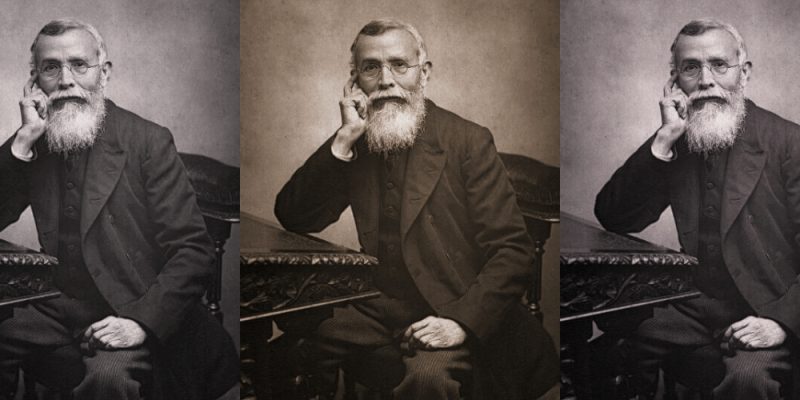

Dadabha Naoroji. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Jehangir, Sorabji (1889) Representative Men of India. W.H. Allen and Co, Public Domain

The House Commons, Imperial Parliament

The Manchester Guardian, in its July 26, 1892, edition, noted the political significance of Naoroji’s election to parliament: “If there is anything corresponding to a conquering power in India, it is in the House of Commons that its centre is to be found.” It also noted that one of India’s own sons would now speak for Indians to Britain and the world, and share “in the sovereignty of the Empire”.

Naoroji’s election dealt a severe blow to Conservative Prime Minister Lord Salisbury, who had controversially asserted that the country was “not ready to elect a black man”. Yet, in heavily working-class Central Finsbury, Naoroji won the seat with a majority of just five votes, earning the nickname “narrow-majority” from his critics. Working-class, liberal Finsbury was ready, but only just.

Given the rather easy resort nowadays among political scientists and politicians alike to complacently accept 19th century racism as the unchallengeable convention, with white racial superiority sanctified by ‘scientific’ research, the uproar against Salisbury across Britain was instructive. Against the undoubted racism of the time, there were also powerful forces for freedom for Ireland, votes for women, economic rights for workers, and a fair shake for the underdog.

Hence, the Newcastle Leader had cause to remind PM Salisbury that “by far the larger proportion of the British subjects are black men”, and that to condemn a man merely for his colour was reminiscent of the “very worst days” of slavery.

Naoroji blazed a trail that led to Indian independence

Naoroji had hardly landed in Liverpool (in 1855) to set up the first Indian business in Britain, when he felt moved to challenge the way British colonial rule drained the wealth of India, causing untold hardship and immiseration, and blocked the aspirations of the educated. He spoke thus, for example, before the East India Association on May 2, 1867, regarding what educated Indians expect from their British rulers, containing an implicit warning of rising discontent:

“The difficulties thrown in the way of according to the natives such reasonable share and voice in the administration of the country as they are able to take, are creating some uneasiness and distrust. The universities are sending out hundreds and will soon begin to send out thousands of educated natives. This body naturally increases in influence…”

Naoroji condemned “the deplorable drain [of economic wealth from India to England], besides the material exhaustion of India… All [the Europeans] effectually do is to eat the substance of India, material and moral, while living there, and when they go, they carry away all they have acquired… The thousands [of Indians] that are being sent out by the universities every year find themselves in a most anomalous position. There is no place for them in their motherland… What must be the inevitable consequence?”

Through Naoroji’s collaborations with British socialist Henry Hyndman, Naoroji’s drain theory made its way to Karl Marx, according to the Indian scholar’s biographer, Dinyar Patel. Hyndman had urged Marx to meet Naoroji because of his analysis of how British rule bled India. A few days later, Marx wrote to a Russian economist of British colonial rule as “a bleeding process with a vengeance,” as the empire “appropriated…more than the total sum of income of the 60 millions of agricultural and industrial labourers of India..”

By the 1890s, despite the formation of the Indian National Congress in 1885 (with Naoroji as a founding member), little had changed. As Pherozshan Mehta, a Naoroji ally, noted in 1892, it was time to bring the movement to Britain. Naoroji must advance the INC’s ‘policy of carrying the war, as it were, into the enemy’s country…’

The ‘war’, it turned out, was to be waged with petitions and leaflets, the pen and the word, not the sword. And Naoroji adopted the mantle of British imperial patriotism in order to educate and shift British opinion on the Indian empire’s ultra-exploitation and exclusion from the benefits of imperial wisdom.

In the House of Commons, at the heart of empire, Naoroji courageously “proposed measures such as free education and the extension of the Factory Acts, supported Home Rule for Ireland in 1892, and also wished to introduce reforms for India, particularly to the Indian Civil Service and legislative councils…” The Factory Acts aimed specifically at working conditions, health and safety, wages, the rights of women, and child workers, in Britain’s “dark Satanic mills”

Naoroji dropped demands for Indian ‘home rule’ in order to build an alliance with progressives and political elites at a time when most Britons knew little of how empire actually worked.

Statue of Dadabhai Naoroji at Flora fountain in Mumbai. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/smz – Colaba-35-c5-3Uploaded by Ekabhishek CC BY 2.0

Naoroji and the Indian National Congress

Ironically, in a previous incarnation, Lord Salisbury, the PM who inadvertently made Naoroji famous throughout the UK, had been the Secretary of State for India (1866-67). In that capacity, he had done all he could to prevent Indian participation in the governance of British India itself, including in the Covenanted Civil Service.

In that regard, Salisbury was violating Britain’s self-declared policy since the 1830s, including the infamous words of the East India Company’s Thomas Babington Macauley. Macauley dismissed Indian culture and learning:

“It is, I believe, no exaggeration to say that all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanskrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgement used at preparatory schools in England.”

On that basis, Macauley inaugurated a Western “civilising mission” through Anglicising Indians through schooling:

“We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population.”

The implementation of the Macauley Minute of 1835 came to haunt the British Raj. Decades later, as Naoroji noted, the pressure from educated and talented Indians was increasing to such an extent that many colonial officials feared a turn to greater radicalism than mere ‘home rule’. A ‘safety-valve’ became necessary to channel discontent, to incorporate educated Indians, and moderate their demands. In a roundabout way, the formation of the Indian National Congress in 1885 was fundamental to the process. In addition, British colonial officials feared that unemployed and discontented Indian intellectuals might provide the leadership of a mass revolutionary movement to overthrow British rule.

Hence, more or less in line with that view, and to hold the colonial line, Lord Dufferin (Viceroy to India) gave a qualified blessing to the INC, despite fearing the emergence of an alliance of educated Indians, elements of the Indian aristocracy, and radical Liberals in the British House of Commons.

Thomas Babington Macaulay. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

“Carrying the war into the enemy’s country”

Hansard reported Naoroji’s maiden speech in parliament thus:

“After a hundred years of British administration—an administration that had been highly paid and praised— an administration consisting of the same class of men as occupied the two Front Benches, India had not progressed, and while England had progressed in wealth by leaps and bounds—from about £10 in the beginning of the century to £40 per head—India produced now only the wretched amount of £2 per head per annum. He appealed to the House, therefore, to carefully consider the case of India.”

More pragmatically, Hansard reports that “He [Naoroji] knew that Britain did not want India to suffer—he was sure that if the House knew how to remedy the evil they would do justice to India…” Naoroji was careful to maximise support for his positions in parliament and country, and kept his support for Indian ‘home rule’ private. He even promoted his motivation as driven by British patriotism.

In another parliamentary intervention, Naoroji criticised opium sales and taxes in India:

“..would this House understand the mischiefs under which India was suffering; then, and then only, would they know how it was that, after 100 years of the rule of the best administrators, and the most highly-paid administrators, India should be the poorest country in the world. He could adduce testimony from the beginning of the century down to the present time to show that there was nothing but poverty in India. That could not be satisfactory to England, who desired that India should appreciate British rule, though how that could be expected he could not understand, seeing that an income of £6,000,000 or £7,000,000 a year was made by poisoning another great people, and that taxes—the most cruel that had ever been conceived in the whole history of mankind, such as the heavy Salt Tax—were imposed. Such should not be the method of British administration, and such should not be the result of British rule. There was no reason why it should be so. If the existing errors and evils were discovered and grappled with, he had no doubt that India would bless the name of British rule.”

In 1893, Naoroji formed the Indian Parliamentary Party within the House of Commons to focus attention on Indian matters. The group went on to have 200 members by 1906. Naoroji was a member of the Royal Commission on Indian Expenditure in 1895. His main aim was to demonstrate that the British empire was draining the wealth of India to the tune of millions of pounds annually and had reduced the ‘jewel in the crown’ to utter desperation and poverty as a result. The “drain theory” of empire was eventually published in Naoroji’s book, Poverty and Un-British Rule in India (1901).

Sumita Mukherjee’s journal article notes:

“Naoroji and Bhownaggree [Britain’s second Asian MP] should not be forgotten or seen as anomalies of the late Victorian era. Although studies of Victorians and racism emphasize scientific racism, xenophobia, class and assimilation, Naoroji and Bhownaggree are clear examples of the range of racial attitudes in existence, and of the high regard many British people had for their Indian colony. Their election in predominantly working-class constituencies demonstrates that racism was not a prejudice held by all uneducated Britons. Moreover, racial prejudice was very apparent in those who were MPs and had power over the Empire..”

Indeed, as Dinyar Patel shows in his excellent biography of Naoroji, racism was stronger among the apparatchiks of the Liberal party and elite than among the working classes.

Dinyar Patel

Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism

Harvard University Press (2020)

Naoroji’s Liberal opponents resorted to “England for the English” rhetoric in their desperation to thwart his campaign. “In their ability to single out and malign Naoroji with racial epithets,” Patel argues, “[Liberal] party officials in Central Finsbury gave stiff competition to the Conservative prime minister”. Where elites across the Liberal-Conservative spectrum vied with each other to show how much of an ‘outsider’ or ‘foreigner’ Naoroji was, thousands of local workingmen “gathered on Clerkenwell Green to protest against.. [the racist anti-Naoroji clique].. and pass a resolution recognising Naoroji as the official Liberal candidate…”

The campaign to prevent Naoroji’s Liberal candidacy was ferocious as rivals sought to play the race card with party leaders and voters alike. Yet, interestingly, such moves drew vociferous criticism at mass meetings in the constituency, with the racists shouted down by local residents.

Nevertheless, Naoroji showed great tenacity and determination in his bid to secure the nomination. “They think they can keep down the mild Hindoo,” he told a British friend. “I will show them.” And he proceeded to mobilise his numerous India-based allies to pepper the British press with articles on Naoroji as the voice of India’s teeming millions, deserving of representation in the Imperial parliament. And Central Finsbury’s Liberal electors lapped up the idea that their candidate for parliament would bring “the blessings.. [of] 250,000,000 [people of] India..”

Naoroji’s opponents were forced to admit that his claim to represent an entire sub-continent was his “trump card”. Naoroji’s Indian allies’ media blitz reached all the way to William Gladstone, the Liberal Party leader.

Also Read: At Last, a Biography of India’s Grand Old Man

To commemorate Naoroji is to write an inclusive, more complex history

Naoroji’s is a remarkable story and one that is largely forgotten. Yet, there is so much to be learned about British society and politics, India, the empire, and the rise of the voices and movements of the colonised and humiliated. In short, Naoroji’s is a story of the making of the modern world with all its twists and turns, and ambiguities. In our polarised times, we may yet appreciate by examples such as Naoroji that passion, cold analysis, and deft political strategies of alliance-building across divides, may yet offer pathways to progress.

Naoroji taught Gujerati literature at University College London, and represented the working-class constituency in which City, University of London, is located. The original mission of the institute that developed over a century into City was “the promotion of the industrial skill, general knowledge, health and well-being of young men and women belonging to the poorer classes”. The University’s motto is “to serve mankind”.

He ventured into the imperial lion’s den, brought the struggle for justice and dignity to the very core of the Raj. The empire was not something that happened somewhere “out there”; its true power, its very beating heart, centred in the Imperial Parliament in London.

The core and periphery of world power were, and are, after all, indivisible. As are our stories.

Inderjeet Parmar is professor of international politics at City, University of London, and visiting professor at LSE IDEAS (the LSE’s foreign policy think tank). He is a columnist at Khabri Baba. His twitter handle is @USEmpire.