Annabel Mehta, Sachin Tendulkar’s mother-in-law, has dedicated her life to working with the Beautiful People of the other half of Mumbai without whom the city would neither exist nor thrive.

Vaihayasi Pande Daniel met the amazing lady who was awarded the Member of the Order of the British Empire for her service to underprivileged communities.

The woman, who stepped up to receive her MBE from Prince William at Buckingham Palace, as her brother, sister-in-law and her granddaughter Sara looked on proudly was tiny and petite.

In her late seventies, silver-haired, she looked classy and gracious in a reddish-brown embroidery-edged salwar-kurta.

She is British.

She is Indian too.

Like her name.

Annabel Mehta, MBE.

You wondered what thoughts and memories must have run through her head as she accepted the British honour.

Did she see her life, up till then, in a quick rewind?

Or was she remembering the milestones of the intriguing, colourful nearly 50-year journey that had brought her all the way to this royal residence?

One of the early founder members of Apnalaya, that began in 1972, and has its headquarters in Tardeo, south Mumbai, Annabel Mehta has devoted much of her life to the running and progress of this NGO that helps all kinds of marginalised people living in Bombay’s vast and mostly overlooked slums, where the daily struggle is inconceivably uphill.

IMAGE: Annabel Mehta with Prince William and the Duchess of Cambridge. Photographs: Kind courtesy Apnalaya/Facebook

Annabel Mehta has dedicated her life’s energies to working with the Beautiful People of the other half of Mumbai, without whom the city would neither exist nor thrive.

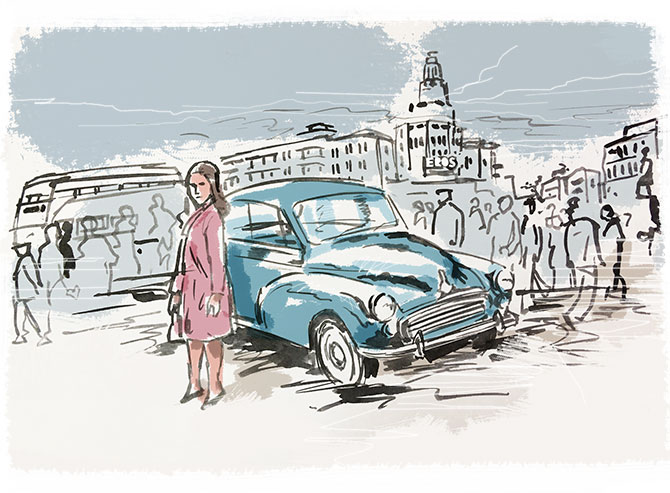

But Mehta’s heroic tryst with Apnalaya and her special India Story actually began, somewhat serendipitously, all the way across the world in Beatles-and-mini-skirt-preoccupied, dizzy Swinging Sixties London.

While completing her postgraduate studies in social administration at the London School of Economics, Annabel Lancaster got to know a young student from Mumbai named Anand Mehta who belonged to a prosperous Gujarati industrialist family and was earning a degree in economics.

It wasn’t long before marriage was on the cards.

Marriage and the opportunity to settle down in India, because Anand had no plans to stay on in England.

Mehta’s family, the Lancasters, who hailed from Worcestershire, near Birmingham — she is the daughter of a chartered accountant turned businessman and has three elder siblings — were not enthralled with this plan that would take their daughter halfway around the world.

In those days, travel to India was both rare and highly expensive. India, effectively therefore very far away, was not entirely unfamiliar to them because Mehta’s father had made it to India once and they also had close business friends in Madras, who happened to know Anand Mehta’s family too.

“Of course, they were not in favour. In those days you didn’t know much… And I was working, had my own little car and had rented a tiny flat. For me also to give all that up and come to India was a major consideration.”

IMAGE: Annabel Mehta with her daughter, Dr Anjali Tendulkar.

But Mehta, 79, was always a determined person, she explains to me, over a cup of tea and a plate of cookies at a trendy Bandra, north west Mumbai, tea lounge. When she makes her mind up about something, like quitting playing the piano as a student of the Royal College of Music, not much can sway her to go off course.

She declares: “My family wasn’t sure. I was sure. I have taken two major decisions in my life. Both of them have been opposed by my family. One was to give up music (piano, because she hated to perform) and one was to come to India. Once I make up my mind, I don’t usually (change it).”

Her mind wandering back to the long ago year when she embarked on a life-changing journey to India, Mehta recounts frankly, with lots of details, how unusual it actually was in retrospect.

The meeting is a charming, fascinating one. Mehta, an elegant, warm woman with a gentle voice and a refined, pleasant-on-the-ear accent, that is still very British, with a few high musical Indian notes, has a wry sense of humour.

She knows how to tell a good story. And underline the humour in it. And she’s frank.

Her story, like many of those times, is a brave one, because venturing to make your home and a new life in a faraway tropical country, with a husband of another nationality, race and religion, was as courageous a migration, as other kinds of global voyages happening at the time.

But as you continue to speak to Mehta, over two meetings, you understand where she was coming from and why marrying an Indian of her choice and staying on in India was exactly the kind of fullness/depth and variety she wanted for her life to be rewarding.

After deciding to hitch her star with Anand Mehta’s, Mehta planned a preliminary visit to Mumbai, then Bombay, where she and Anand Mehta got engaged.

IMAGE: Annabel Mehta, right, with her famous son-in-law at the Apnalaya office.

Some months later, in 1966, the plucky young woman and her ‘dowry’, a Morris Minor 1000, boarded a French Messageries Maritimes ship in Marseilles, southern France, bound for Bombay. The journey, via the Suez Canal, took ten days and was rather horrid, Mehta remembers.

The voyage resulted in marriage in December 1966.

Buying a car in India in those days was tough — “you waited seven years to buy a Fiat!” — and Anand felt his future wife would need a car to feel slightly independent as she adjusted to her new role in Mumbai.

Bringing any car to Bombay was a big enterprise. Cars and air tickets to India, then, were nearly the same price (subsequently air tickets became a fraction of the cost of a car). On arrival into India, the importer of the vehicle was charged 100 per cent duty and had to sign a bond to not sell it for 10 years.

After marriage, she settled down in the spacious Mehta family bungalow in Breach Candy, south Bombay, opposite the erstwhile American consulate. The Mehtas were a landed family with several business interests.

“When I got here of course, I found that his family was so similar to my family.”

Mehta recalled that the Mehtas were very Western-looking with many commonalities with her own, both being business families. On her husband’s mother’s side various members had studied in England and Heidelberg.

Her mother-in-law’s father had worked in the British civil service rising to nearly collector level. “She (her mother-in-law) welcomed me like a fifth or fourth daughter and the whole family and friends were so welcoming. I had no difficulties.”

She discovered that she felt quite at home with a lot about India, where life still had a lot of British influences. Indian schools back then had a strong Western focus and there was much in common, in backgrounds, and the society, between those educated in Britain and those educated in schools in India.

Also while she was studying in London she had always preferred to hang out with a totally polyglot crowd, but her Indian group of friends were always the most special because she felt most at ease with them.

“I reckoned it was because we shared the same sense of humour.”

IMAGE: Annabel Mehta with her grand-daughter Sara Tendulkar after receiving the MBE.

Finding an identity of her own and making a mark in a city like 1960s Bombay must have been incredibly challenging for Mehta. As a ‘foreigner’ she was not allowed to work or draw an income. “You got a P form to leave the country. And a license to work from the government. All these things.”

She makes light of the struggle, remembering: “I knew I wanted to do something. I am not the sort of person who can do nothing all day — (like just) read a book, watch television, or go to tea or coffee parties or whatever it is people do.”

“Or play cards! My mother-in-law, to get away from her mother-in-law, started playing cards every day. My husband was a champion bridge player. He played for India many times. He used to play cards every evening. But I never have learned how to play cards.” Laughs.

Her ‘dowry’ actually provided the escape it was intended to. Having a set of wheels, which she drove herself, in Bombay was more valuable than perhaps she could have imagined.

In the late 1960s Bombay had just two Morris Minors. And one of them was Mehta’s. Her Morris became a famous moving landmark of the city.

Whenever Mehta, who belonged to the city’s miniscule expat community, got about town, all quite easily figured where she had reached and who she was, because her car heralded her arrival.

“Everybody knew where I was. They would see me — I saw your car parked outside… you know. What were you doing there?!” she recollects, laughing uproariously.

She soon discovered she could, since she had a car, volunteer, off and on, for an NGO that distributed excess wedding food to the poor or hungry both at institutions and to those living on the pavements.

Mehta took time off in between to have two daughters — Anjali Tendulkar, cricketer Sachin Tendulkar’s paediatrician wife, was the elder.

She lost a daughter when the little girl was six. Mehta speaks poignantly, now, many years later, about the great pain of losing a child and how tough had been the battle to try and save her.

Suffering from a sudden allergic drug reaction, they were unable to fly her out of Bombay for special treatment in the UK in time.

Volunteering at the food-distributing charity led to further work with the newly-formed Spastics Society of India and subsequently to a meeting with Shanta Gupta, the then president of Apnalaya.

IMAGE: Annabel Mehta with Prince William at the MBE ceremony.

Apnalaya was begun by Tom Holland, an Australian consul general, and his wife Judy Holland.

It was first called the Holland Welfare Centre and was an organisation that provided food and daycare for the children of migrant labour at Nariman Point.

Nariman Point had just been reclaimed from the sea and enormous crews were toiling at this work and the buildings that came up there.

Holland was disturbed by the army of children hanging about, neglected as their parents worked all day and he created a shelter for them.

Mehta began volunteering in 1973 by which time the Hollands had left India. Her work at Apnalaya, some of the time as treasurer, slowly absorbed Mehta more and more, even as the organisation grew.

It moved to its present location at New Jaiphalwadi slums, Tardeo, behind the swanky 60-floor Imperial Towers, where it began a balwadi to care for slum children and later a health centre a little further away.

It slowly expanded its approach to social work involving itself with the community as a whole. They branched out and established themselves at Shivaji Nagar, Govandi, on the border of the Deonar abattoir and dumping ground, north east Mumbai, a community that desperately needed a few protectors and spokespersons and where the work that an NGO could do was almost limitless.

Bit by bit, Apnalaya established itself in multiple slum communities across the city, coming in like an extended benevolent family member to the people, helping in whatever way they can.

Mehta enjoyed her social and family life in India. But like many foreigners she found the yawning chasm between the rich and the poor pretty hard to tolerate. But instead of it scaring her off and sending her home, Mehta felt she had to pitch in.

That was the only way she felt she could feel emotionally comfortable living in India and yet also strike a balance between herself and her environment

“Balance was probably most difficult thing to do.”

She remembers an initial incident that put that in sharp focus. Bombay in those days had prohibition. But still people stocked their homes with liquor via bootleggers.

“It cost more to buy a bottle of whiskey (from the bootlegger) than I paid my cook for a month and I had a huge row with my husband over that. He said, ‘You just have to learn to live with it in India’. And I think you do have to learn to live with disparity the whole time. Some foreigners who come here can’t manage that.

“I think the other thing that you have to teach children when they are very little is that life is not fair. It’s not fair that that child has a better doll than I have. That is something you have to teach people. And that some countries are more fair than others. In India life is not fair… extremely hard life.

“But people in India seem to somehow manage to rise above it and sustain it whether it is religion, Hinduism teaches you to accept. Yes they don’t have any bitterness and that’s what I like so much.”

“I coped with it by doing whatever I could. Neither my husband nor I live an ostentatious lifestyle. It is only now that my daughter is married to a young man, who had nothing when she married him, hardly, and now he is an extremely wealthy individual.”

IMAGE: Annabel and Anand Mehta at the Wankhede stadium. Photograph: PTI Photo

If the Indian disparity goaded Mehta into investing her heart into the work she did at Apnalaya, she basked in India’s diversity, having grown up in a part of England that was so white that you could not even have coloured friends.

“All this diversity I loved. I loved the tolerance, which is declining. The religious tolerance, the diversity. That opened my eyes. Coming to India — okay, you don’t have any Chinese and Africans — but you have such diversity in society.”

In illustration she relates how she is having electrical work done at her Bandra home and how she has to deal with a Michael, Sharad, and a Mohammed.

She chuckles, “It’s Amar, Akbar, Anthony all over again. I don’t know whether it (the diversity of India) changed me, but it enabled me to live in an environment that I was happy with. I never liked the constricting environment of England. It was too uniform.”

Her world-famous cricketer son-in-law helps her with her work when he can and is always she says raising awareness for Apnalaya.

“He has been very supportive. I don’t ask him to support Apnalaya. Within a family, and particularly with in laws, you have to be a little bit careful. But he really started taking an interest when his father died (in 1999). He wanted to do something in memory of his father. He asked me one day what does it cost to sponsor a child for school because in those days we used to get sponsors for children in school.”

Sachin began giving lump sums towards educating hundreds of children. He also helps bail out the organisation if they have certain financial or other kinds of difficulties or needs help meeting people of influence for an issue.

He asks his friends to support Apnalaya and often pledges amounts at events. He has visited Apnalaya’s Shivaji Nagar office several times and met the staff on another occasion.

“He is a very private person and he keeps as much (details of the work he does) as he can to himself and it is only publicised if it necessary.”

She adds with a broad smile: “When we first knew Sachin, when he used to come home, he is a very good mimic. One of my first memories of him and Apnalalya is him mimicking how I go off to work. I am one of those people always in a hurry. So he knew about my involvement right from the start. (He would mimic) how I rush out every morning.”

She laughs heartily as she recalls the shy young man who entered her daughter’s life, quite accidentally, five years before Anjali and Sachin actually married and Anjali gave up her career in medicine to be there for him, although now she is slowly once again involving herself in medical work and Mehta is hopeful she will go back “in a big way.”

Mehta had never ever expected an MBE for her work.

But when in mid-2017, the UK deputy high commission — who became more aware of her work after Prince William and his wife Kate came through in 2016 and rode a bus with Apnalaya children — contacted Mehta to ask if she would like to receive such an honour (prior permission is always sought), she was deeply moved.

More so, because her father N G Lancaster, before her, had been awarded an MBE for his work in organising Birmingham’s industrial wartime efforts and she remembered his pride in earning the honour. “Well… I must say it is sort of an extraordinary feeling.”

When one meets her, for the second time, at the Apnalaya headquarters, to discuss her work further, you are meeting quite a different Mehta, who smiles much more and is full of an optimism.

Apnalaya is definitely her second home, if not her first.

It’s a place where she cheerfully belongs, even if she doesn’t appear anything like anyone else in her environment, in spite of a brave command over Hindi.

It’s a place where her heart belongs.

And the place that celebrates her decision to stay on in India and lead a life, as she terms it, modestly, that “doesn’t harm other people and that, as far as possible, does some good to other people.”

Mehta talks about what Mumbai-ites do not know about slums, about how it is embarrassing to have a bathroom large enough to accommodate a few slum families (“You have to come to terms with it — the lack of parity — philosophically… because you can’t help where you were born”) and how what working in Apnalaya has done for her is “really to show me how wonderful everyone is.”

She says she often, upsettingly, encounters a lot of ignorance from well-to-do citywallahs about the people living in slums. She is shocked how so many believe that those living in slums are there because they deserve to be.

“A lot of people think that all people who live in slums are criminals, alcoholics, beating up their wives or not sending their children to school or whatever. What I try to say is that people living in slums are just like you and me. There are nice ones, nasty ones, good ones, bad ones, corrupt ones, honest ones. You know they are people!

“So too generalise about slums and people living in slums is (so wrong). And they do it all the time. The perception is that because you live in a slum you are lazy. The public perception of slum dwellers is: Us (vs) slum dwellers. Like two different species. But we are not! Half, or whatever the statistics are — whether it is 40, 50, 60 per cent — of Bombay’s population live in slums or on the pavements.

“Do they any choice? Does the government provide them with low cost housing like they do (say) in the UK… And now with the political climate as it is, slum dwellers will be labelled as Muslims, or from UP, Bihar or South India. Anything other than (someone like) me!”

But the greatest battle Mehta faces in her work with Apnalaya is the struggle to contain her frustrations at often being powerless, she tells you almost teary-eyed and momentarily slightly weary, her voice pained.

This is the disappointment she feels when she sees the familiar faces of those she has come to know, through her organisation, and whose stories, even with lots of help from Apnalaya, don’t or can’t get significantly better.

Or because, as she examines it philosophically, change is very incremental and only after several generations can it be effected, always hoping there is no backwards slide in the intervening time.

Recalling a particular case relating to a mentally and physically challenged girl named Sunita, Mehta says, “The poorer you get the more difficult it gets to deal with any problem. And really, to see Sunita’s face, I think I think how much can you do for someone? That was one of my dilemmas living in India.

“How much can you do? My husband and I didn’t have a lot of money to give away. And money isn’t cure for everything, although it is a jolly, big cure.

“But how can you help people to cope in difficult circumstances I think probably what underlies my commitment to work here.”